|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

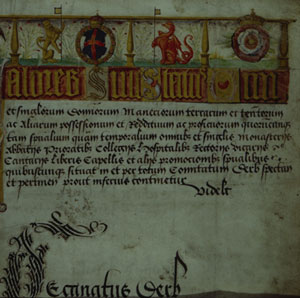

The dissolution of the monasteries (1/2) The Dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII (1509-47), brought an end to monastic life in England and Wales; Scotland’s monasteries continued until the rejection of papal authority there in 1560. Through the Act of Supremacy in 1534 Henry VIII declared himself the head of the Church in England; any who opposed this were charged with treason. Henry sought to assess the state of monastic life in the country through a rigorous investigation of every house. This was said to be in order to uncover and suppress dissolute living, but the need for money lay behind these pious motives.

Henry first ordered an evaluation of all the

property belonging to the church in England and Wales; this survey,

known as the Valor

Ecclesiasticus, estimated that the monasteries had a net

income of £320 000, although the real figure was probably

closer to £400 000, ten times greater than the Crown’s

annual income. Thereafter, the king sent commissioners to conduct

a gruelling visitation of every religious house and compile a report

of their reprehensible conduct. Their findings were entered in the

infamous ‘Black Book’, which was read before parliament

in 1536. This gave a distorted picture of monastic life, reporting

that two thirds of the monasteries were filled with debauchery;

however, it provided the king with the necessary ammunition to effect

the first stage of the Dissolution - the suppression of houses with

an annual income below £200.

This first Act of Suppression provoked uprisings in the North known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. The insurgents maintained that they were not staging a rebellion but a movement in defence of the Church and against those who had given the king evil counsel. The uprising began in Lincolnshire and soon spread to Yorkshire, where it was led by a local barrister, Robert Aske, who was later hanged at York for his actions. Whilst a number of religious joined the insurgents, not all were willing participants; the monks of Kirkstead, Lincolnshire, were warned that should they not join the rebels their buildings would be burned. Sawley (right) surrendered in May 1536, but with the support of the locals the monks returned in October of that year and put up an active resistance to the royal commissioners. Sawley emerged as a hotbed of rebellion, but despite their opposition the abbot of Sawley was arrested in 1537, charged with treason and sentenced to death; it is not clear if he actually died of natural causes before this sentence was carried out. Following the deaths of some two hundred insurgents in 1537, measures were taken to effect the suppression of the greater houses. Commissioners used persuasion, coercion or force to obtain the ‘voluntary surrender’ of each community, and in chapter- houses throughout the country monks appended their names to surrender deeds, sealing their fate. Keys were handed over to the commissioners, the monastery’s possessions allocated to the Crown, and the monastic buildings destroyed to prevent any attempt at a revival. In 1539 Henry legalised and legitimised his actions by an Act of Parliament. |